Today I visited the Chichiri Museum in Blantyre, also known as the Museum of Malawi, which was first opened in 1957 at Mandala House, the early colonial era building that is now home to La Caverna, as discussed in my second blog in this series. In 1966, the museum was reopened in its new home by then first Prime Minister of Malawi Hastings Kamuzu Banda, in one of his earliest acts after Malawian independence in 1964. Banda’s silhouette looms large over Malawian history, and his role in shaping the country’s trajectory after independence deserves its own focus, but he also features in one of the first exhibits in Chichiri.

Besides a giant image of Banda sit two of the most important

documents in Malawi’s post-independence history. First, dated 6th

July 1966 and signed in Blantyre, is the oath Banda signed as he became President

of the newly announced Republic of Malawi. He had previously served as Prime

Minister in the first cabinet following independence in 1964, but a power

struggle between Banda and his colleagues resulted in a cabinet crisis in

which Banda expelled his rivals from Parliament, and began to consolidate his

power. The power grab was completed on his ascension to the Presidency on 6th

July 1966, and in the following years he tightened his grip further. The second

document on the right of Banda’s image in the exhibit is the oath he signed

exactly five years later, on 6th July 1971, this time as “President

for Life”.

|

| The Hastings Kamuzu Banda exhibit, a giant of Malawian politics |

Unlike many other dictatorial leaders in post-independence Africa, Banda would not live up to his new moniker. He served as President from 1966 until 1994, three years before his death in 1997. Many political experts point to the end of the Cold War as the beginning of the end for Banda’s rule. He had ruled on an expertly pitched anti-Communist agenda, which earned him the support of Western powers, as well as a close relationship with Apartheid-era South Africa. However, when the Soviet Union collapsed and Apartheid was finally ended, that international support dried up and he was left in a much-weakened position. In 1993, a national referendum revealed the people wanted an open democracy, and in 1994 he was voted out of power. His legacy continues, however, as his Malawi Congress Party remains a key player in national politics, and is home to current President Lazarus Chakwera.

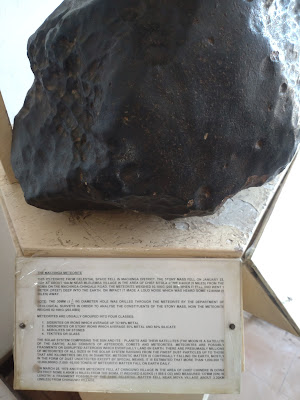

But the Museum of Malawi offers a lot more than the Earthly

tales of Hastings Banda and his political exploits. Next to this exhibit is an

otherworldly display, the Machinga Meteorite. The Machinga Meteorite struck the

southern province of Malawi on the morning of January 22nd 1981,

and to date is the largest meteorite recovered from Malawi. It has inspired art

and science across the country since it first arrived, and one of the most

popular fictional children’s books in Malawi is based on a schoolgirl who

wants to learn about extra-terrestrial objects, and ends up trying to track down

the stolen Machinga Meteorite.

|

| The Machinga Meteorite |

Beyond the main exhibition are a lot more historical artifacts tracing human history from the earliest travels of ‘homo erectus’ through to the modern day. The ancient pre-historic exhibits were particularly fascinating, as homo erectus, one of homo sapiens’ earliest predecessors, supposedly emerged in Africa approximately 2 million years ago. Some of the earliest evidence of homo erectus was discovered in northern Malawi, around the village of Karonga which sits along the shores of Lake Malawi, and this same area is also host to a large archaeological find from the stone age, approximately 700,000 years ago.

A large portion of the museum is also dedicated to the

traditional tribal histories of Malawi, and the fascinating cultural rituals

that have been practiced by the many different peoples that make up the

Malawian populace. Of course, many of these groups came into direct contact

with European explorers and settlers in the mid-19th century, which

changed the trajectory of the land permanently. David

Livingstone’s journeys across southern Africa are captured in detail, with

evidence of some of his earliest meetings with local people. Livingstone

brought Christianity with him, and as this new religion spread many of the traditional

beliefs and rituals were lost. Some remain today, and continue to shape

Malawian culture, and the museum hosts historic reenactments to demonstrate

these important practices. My guide around the museum showed me a video of

members of the Gule Wamkulu

ritual dance group, wearing artifacts from the museum as part of their

display. You can watch another

recreation of this dance here. He also demonstrated some of the traditional

medicines used by different ritual healers in historic groups across the

country. Many of these medicines were aimed at identifying witches and wizards,

who could do harm to loved ones if not addressed. Medicines were mostly amulets

or items of clothing that could

be blessed or cursed by traditional doctors, to protect the wearer or harm

the attacker.

|

| The Gule Wamkulu traditional attire, just one of many cultural groups represented in the Malawian population. |

|

| David Livingstone's journeys through Southern Africa. On his route he encountered many different peoples and cultures, but his journey also sowed the seeds of the modern makeup of the region. |

It is important to continue to shed light on these activities, as so many of them were lost in the colonial period and beyond. In urban Malawi today, many of these cultural traditions are no longer practiced. In rural areas some still persist, which can have extremely dangerous and negative consequences, for example in relation to the treatment of people with albinism in certain areas of Malawi. However, they also represent an important cultural and religious history that European colonialism tried to eradicate. Outside of the museum stands some impressive colonial-era technologies, such as the first heavy goods tractor and train engine that were transported to Malawi from the UK in 1906, to move goods from the port in Nsanje up to Blantyre and Lilongwe. Next to them was a “Europeans-only” bus that operated until the end of the colonial era, transporting white Europeans around the country in ways that locals could not take advantage of. This colonial legacy birthed modern Malawi and permanently changed the social and cultural relations of the people who call this country home. As a historical museum, Chichiri does its best to navigate the pre-colonial, colonial, and post-colonial stories of an ever-evolving populace. I am not the person to judge the level of its success in this regard, but I am grateful to have expanded my own understanding of a place I'm quickly growing to love, just one week after I have arrived.

The Museum of Malawi does a good job of capturing the

complex and varied histories of the people of Malawi, despite its limited size

and budget, and is a recommended visit for getting a better understanding of

the way that modern Malawi came to be.

|

| The "Nyasaland Transport" bus, which was reserved for Europeans only. |

As I was leaving the museum an older man came up to me with a smile and asked where I was from. I told him I was from the UK, and I was studying at Loughborough University. He stopped me and said he had been to Leicester many years ago, and that he loved the UK. He asked about my reasons for coming here and I explained my research. We talked for a good ten minutes before he shook my hand and waved a goodbye.

“I’m sorry, my friend, but I have to go now. It is a

pleasure to have you in my country, as I once was in yours. Welcome to Malawi,

it is a complex place. Hopefully you have learned some more here today.”

I certainly did, but there is a lot more learning to be

done.