I wasn’t expecting to follow up my first blog post from Blantyre quite so soon, but I’ve had another day exploring the city and one of the places I visited revealed more about the colonial history of Blantyre, and its link to the Blantyre Mission. La Caverna is an art gallery, café, and archive of historical art and documents from Malawian history. It’s setting, the beautiful Mandala House perched just a short walk from the bustling city centre, was built in 1882 and is the oldest European building in Malawi. As that moniker may suggest, the history of the house itself is a complex one.

Just two years after the Blantyre Mission set up camp in the

grounds of what is now St Michael and All Angels Church in 1876, the African Lakes Company began laying

the groundwork for Mandala House. The African Lakes Company was set up with the

expressed goal of working closely alongside the Presbyterian missionaries such

as those on the Blantyre mission, to expand Scottish influence in business as

well as in matters of religion across southern Africa. Today, Mandala House

serves as a reminder of this colonial history, and as I wandered around the art

exhibits and read one of my newly purchased books from

its shop, I began to dive deeper into the tale of the Blantyre Mission, and its

deep ties to British colonisation of Nyasaland, the name they gave to modern-day

Malawi.

|

| Mandala House, host of La Caverna and the Mandala Cafe |

In an article for The Society of Malawi Journal,

provocatively named “A Loathsome Little Brute”, Professor Kenneth Ross of Zomba

Theological College reflects on one of the key figures of the Blantyre Mission,

Alexander Hetherwick (the Reverend quoted in my

previous article, identifying St Michael and All Angels as the first permanent

church constructed in Sub-Saharan Africa). Hetherwick was a core component of

the Blantyre Mission, spending 45 years in Malawi and receiving a CBE for his “services

to empire” before returning to the UK in 1928. He was also the key driver of

British expansion during the “Scramble for Africa”, due to his fear that the

Blantyre Mission would fall under the rule of Portugal, which was expanding

in neighbouring Mozambique. I was unaware of the extent to which lobbying

from the Blantyre Mission forced the hand of a previously

uninterested British government into taking control of Nyasaland. The UK

government was more concerned with South Africa and Rhodesia, and did not want

to take on additional responsibility for land that Prime Minister Lord

Salisbury thought would result in “risking tremendous sacrifices for a very doubtful

gain”.

Nevertheless, Hetherwick persisted. He was afraid that the Portuguese

would take control of the area and that this would do immense damage to the

Blantyre Mission’s capacity to convert local people to the Presbyterian church.

When the African Lakes Company offered to take on governmental responsibility over

Nyasaland, much like the East India Company had across the Indian Ocean before it, Hetherwick wrote a

scathing attack on the company and called for the British government to step in

instead. He also prevented Cecil Rhodes from expanding his British South Africa

Company. As Professor Ross argues, British colonial rule over Nyasaland would

have looked very different, and maybe not existed at all, without Hetherwick.

He is arguably one the most important actors in the establishment of the

imperial Protectorate on 14th May 1891 (the same

year the construction of St Michael and All Angels was completed).

What followed the establishment of the Protectorate was 73

years of British colonial rule. Although the colonial administration was

capable of brutality and repression in order to maintain its power (as seen in

the crushing of the Chilembwe Uprising

of 1915), Britain was never too enthused about this particular colonial

asset, which became known as “the

imperial slum”. Today, Malawi remains one of the

poorest countries in the world, and a large portion of the blame for that can be laid at

the feet of the British policy to recruit Malawian men to send to the more

lucrative mines of South Africa, which, as Hetherwick would later himself accuse,

removed vital members of the workforce from Nyasaland and left the country

dependant on its neighbours. The seizure of land by European settlers from

native people also reshaped the future land use and ownership that can still

be seen in Malawi today, which is something I

will explore further in my thesis research. For example, the large colonial tea and tobacco estates that were created under British rule were transferred to Malawian elites at independence, and remain in the hands of the powerful.

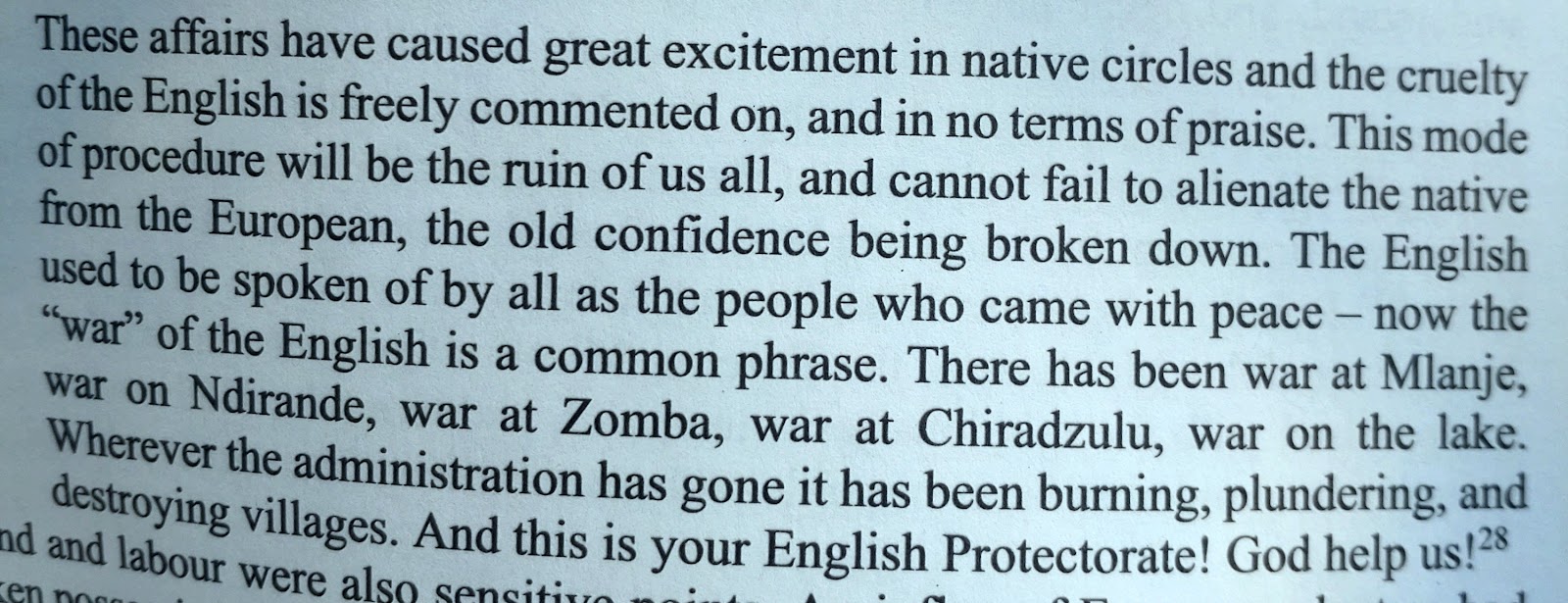

Having been one the core people at the heart of encouraging British colonialism in the area, Hetherwick was a staunch and vehemently outspoken critic of British rule for the rest of his time in Blantyre. He was particularly shocked by the use of collective punishment of communities deemed to have stepped outside of the Administration’s boundaries, on one occasion in 1892 writing to the British government the following passage:

|

| Hetherwick writing to his friend Archibald Scott in 1892 |

He was also largely supportive of the Chilembwe Uprising

when it occurred in 1915, and when questioned by the colonial Commission of

Inquiry after the rising affirmed his support for freedom of the natives to

study religion in the ways they saw as best suited to themselves. He took the

opportunity, when discussing with the Inquiry, to accuse the European powers of

open racism and prejudice.

Alexander Hetherwick was a complicated man, who perhaps more

than anyone else is responsible for the shaping of Malawi’s colonial history

and Britain’s role in influencing the modern Malawian state. A driving force behind

the push for colonialism during the scramble for Africa, he appeared far more

concerned with the threat of other European powers in his little corner of

Blantyre than of the self-determination of the people he claimed to be working

for. He himself was full of the racism and prejudice he accused the "English Protectorate" of, and he too assumed that his own worldview was the correct one without self-reflection. When he got what he wanted, he was horrified by the abuses of power and

the violent repression of colonialism in the land that he called his home for 45

years. This messy and sordid history is one that few white

Europeans like myself are exposed to in any great detail in our schooling, and seeing it up close

should remind us of its continued effects on global social and political

relations today.

One particular exhibit in the archive at La Caverna

that caught my intention was a notice from a 1895 newspaper. It was an amusing

call to action, a reward offered by an unnamed British man of £100 to anyone

who could tame a zebra for use as a “beast of burden”.

|

| The notice from "A gentleman in England" on the virtues of introducing the zebra as a beast of burden... Why had nobody else though of that!? |

Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs, and Steel puts forward a

theory in its description of how the modern world came to be, that one of the

core reasons behind European colonial dominance in the early modern period came

from the domestication of the horse, which prior to the combustion engine was the

equivalent of a tank, a lorry, a motorbike, and any other tool to travel

quickly or carry heavy loads you could imagine. This, he argues, was not due to

a greater European intelligence, but rather due to the fact that the horse

itself that was native to the steppes of central Asia was more easily domesticated

than other similar animals in other parts of the world. Zebras are too feisty,

too aggressive, and no one to this day has managed to domesticate them for use

in a way that we use horses.

It's not a bad idea, if you see someone using a horse to carry

their supplies for them and you happen to have a herd of wild zebras nearby, to

try to domesticate them yourself. But what is interesting about this little

notice is the arrogance with which a British man, several thousand miles away,

can decide that in fact he has solved the issues facing Malawians in their

homeland that he has likely never visited. That arrogance formed the basis of

the colonial project, and it continues to shape the world today.

It is hard not see the parallels with the work of the international

humanitarian sector, which talks a big game about “skills training” and “capacity

development” in disaster- and conflict-affected areas around the world. Indeed,

one of the activities I will be undertaking whilst here in Malawi is to run a QSAND training workshop with members of the

Shelter Cluster. Now, this was a tool developed by professionals in the

humanitarian and construction sector, which offers a useful framing for

decision-making in reconstruction activities and will hopefully be able to add

some benefits to ongoing activities in the Cyclone Freddy response and beyond.

It is also true that this workshop will be run in collaboration with local NGO

staff, who will help to shape the key areas of discussion in order to enable sharing

across different organisations. This workshop will be more of a learning opportunity

for me than the other way around, and the hope is that with what I learn from

talking to those engaging in the projects I am able to improve what QSAND can

offer. That’s how collaboration and sharing should work.

The sector has taken great stock of its own role in redefining the colonial context and in moving away from traditional paternalistic approaches to aid. However, there remains a "white saviour" complex in a lot of international humanitarian practice, which has not been appropriately addressed. This can lead to explicitly, violently harmful outcomes such as was seen in the Oxfam sexual exploitation scandal in Haiti or the horrific deaths of dozens of children in Uganda because of the missionary Renee Bach, who portrayed herself as a doctor despite having no medical experience. But it can also have less obvious impacts that influence the way international staff interact with their local counterparts. Critiques of "aidland" have led to increasing numbers of international organisations encouraging staff to work much more closely with local actors, and the localisation agenda has made modest steps towards addressing this. There is still a long way to go, but my experience with shelter professionals has shown me that people are aware of these issues, and are working to try to do better.

But as a sector, we need to make really sure that we’re not

simply telling people to tame their zebras.

Tomorrow I will begin my fieldwork research in earnest. Until then, I will continue to think about how this remarkable history is playing out today for all of us, not just in Malawi but around the world, and how we can build on the foundations we have to get out of our siloes and work collaboratively. That is the only way to find solutions to the crises we face together.

No comments:

Post a Comment